Remember the days when toy cars were simple and fun? Basic contraptions with four wheels, a tiny body on a plate, and endless fantasy plays in which we were everything from race drivers to cops to mechanics. The last role fell upon those with the more advanced cars with inertia wheels (an electric motor toy was the equivalent of a Porsche 918 in real life today).

That tiny mechanism worked wonders in keeping the car moving over the floor, carpet, pavement, and whatever flat, hard surface it was rolled on. The idea is genius simplicity: push the car along, and the axle spins. The gear on the tiny rod connecting the two wheels would transfer the motion to a smaller gear that spun the flywheel.

The physics behind it is elementary: the rotating mass of the inertia wheel has enough energy to keep the disc spinning, thus transferring the movement to the driving wheels through the ‘gearbox’ (more of a transfer case, actually), thus enabling the toy to keep moving.

Using flywheels in real-life cars is not something new – most combustion engines employ one to keep the crank spinning smoothly between power strokes. But putting an inertia wheel in a passenger car isn’t that common. It has been done in Switzerland, but in buses, not cars, with satisfactory results for the era (the 50s).

The inertia wheel wasn’t the primary power source for the vehicle. Still, it was used as a backup and engaged only under specific circumstances. For instance, the Swiss (developing their trolley bus network back then) used the inertia buses on routes where powerlines weren’t installed continuously from one end to the other.

The vehicle uses electric lines to power its motors and also spin the big inertia wheel. When the bus reached the point where the power lines ended, it simply coasted under the momentum stored in the big rotating mass of the flywheel.

Well, some people – particularly gearheads – don’t stray from their inner four-year-old too much and are always fascinated with toys, regardless of size. And what better team to turn a childhood memory into reality than the lads from Garage 54? The Novosibirsk-based Siberians fitted a Soviet Lada (what else other than) with a hefty hunk of metal and gave it a spin.

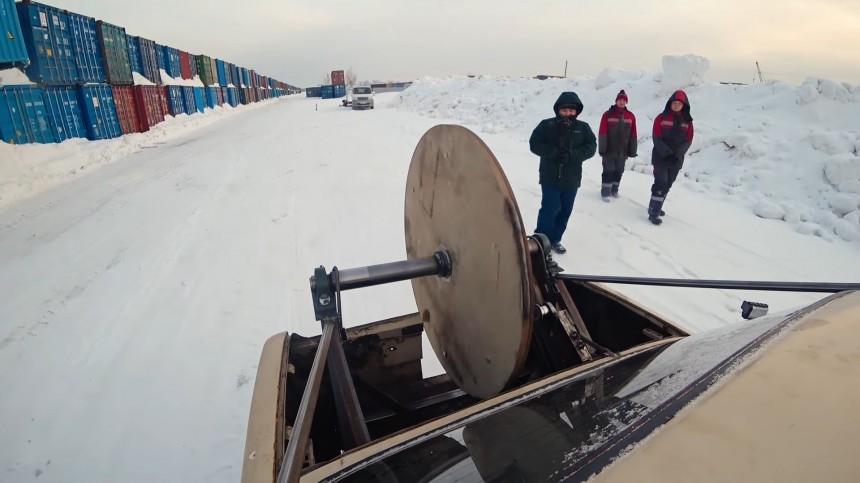

Four hundred fifty pounds (200 kg) of steel discs built from two 40-inch-diameter / one-meter sheets (one is a 1”, the other a 2/3”) riveted together. Remember, this is Russia, so the most reliable assembly installation solution is eyeballing it.

The Lada was hacked up to accommodate the spinning steel slab over its trunk.The rear-wheel drive car was fitted with a second differential to transfer power from the 1.2-liter inline-four engine (59 hp, 64 lb-ft / 60 PS, 84 Nm) to the flywheel.

Look at the build in the video below; the principle is straightforward: the driveshaft coming out of the gearbox doesn’t run straight through the regular differential. In front of that, a second diff turned 90° to the side takes in the engine torque. Think of it this way: what used to be the output (axle shaft of the second diff) is now the input and the former pinion shaft has become a power takeoff that spins the inertia wheel via a set of pulleys and V-belts.

When the car is moving under engine power, the flywheel on the back picks up speed. When the driver disengages the clutch or shuts down the four-cylinder motor completely, the Lada will coast along thanks to the inertia stored in the big lump at the back. The results are impressive if nothing else.

With the added masses of the rigs, the 2,100-lbs Lada (950 kg) is around 1,500 kg (3,300 lbs). This is just a personal estimate, considering all the extra metal put on. When coasting over snow from idle, the car comes to a dead stop In just seven meters (21 feet) – without the inertia wheel getting any engine power.

The Russians then repeated the test, but the flywheel belts were put on this time. The outcome was remarkable: on inertia power alone, the Lada dragged on for 123 meters (375 feet), nearly 18 times more than in the first run. Granted, I wouldn’t recommend trying this at home – or anywhere else. Even at those low speeds, the chunk of steel carries enough potential energy to create a huge mess if anything goes wrong.

For an extra bit of fun, the Garage 54 boys played it like they were in kindergarten again: with the Lada jacked up, wheels in the air, engine running, flywheel spinning, they dropped the car on the ground (at which point the piston power was cut off). Surprisingly, the inertia did its thing and pushed the Lada 66.5 meters / nearly 203 feet.

And remember, the tests were conducted at idle speed in first gear. Should we wait for a second round of trials, with a properly set up and balanced assembly running at highway speeds? It would almost be like child’s play, wouldn’t you say?

The physics behind it is elementary: the rotating mass of the inertia wheel has enough energy to keep the disc spinning, thus transferring the movement to the driving wheels through the ‘gearbox’ (more of a transfer case, actually), thus enabling the toy to keep moving.

Using flywheels in real-life cars is not something new – most combustion engines employ one to keep the crank spinning smoothly between power strokes. But putting an inertia wheel in a passenger car isn’t that common. It has been done in Switzerland, but in buses, not cars, with satisfactory results for the era (the 50s).

The vehicle uses electric lines to power its motors and also spin the big inertia wheel. When the bus reached the point where the power lines ended, it simply coasted under the momentum stored in the big rotating mass of the flywheel.

Well, some people – particularly gearheads – don’t stray from their inner four-year-old too much and are always fascinated with toys, regardless of size. And what better team to turn a childhood memory into reality than the lads from Garage 54? The Novosibirsk-based Siberians fitted a Soviet Lada (what else other than) with a hefty hunk of metal and gave it a spin.

The Lada was hacked up to accommodate the spinning steel slab over its trunk.The rear-wheel drive car was fitted with a second differential to transfer power from the 1.2-liter inline-four engine (59 hp, 64 lb-ft / 60 PS, 84 Nm) to the flywheel.

Look at the build in the video below; the principle is straightforward: the driveshaft coming out of the gearbox doesn’t run straight through the regular differential. In front of that, a second diff turned 90° to the side takes in the engine torque. Think of it this way: what used to be the output (axle shaft of the second diff) is now the input and the former pinion shaft has become a power takeoff that spins the inertia wheel via a set of pulleys and V-belts.

With the added masses of the rigs, the 2,100-lbs Lada (950 kg) is around 1,500 kg (3,300 lbs). This is just a personal estimate, considering all the extra metal put on. When coasting over snow from idle, the car comes to a dead stop In just seven meters (21 feet) – without the inertia wheel getting any engine power.

For an extra bit of fun, the Garage 54 boys played it like they were in kindergarten again: with the Lada jacked up, wheels in the air, engine running, flywheel spinning, they dropped the car on the ground (at which point the piston power was cut off). Surprisingly, the inertia did its thing and pushed the Lada 66.5 meters / nearly 203 feet.

And remember, the tests were conducted at idle speed in first gear. Should we wait for a second round of trials, with a properly set up and balanced assembly running at highway speeds? It would almost be like child’s play, wouldn’t you say?